The classified ad in the Dayton newspaper sought someone for “Plain sewing”. Young Ida Holdgreve, an accomplished seamstress, figured she could do the job. She applied and was hired. However, the ad in the Dayton newspaper had a spelling error. “Plain” sewing should have read “plane” sewing. Twenty-nine year old Ida Holdgreve had applied for, and gotten, a job as head seamstress at the Wright Brothers Airplane Factory.

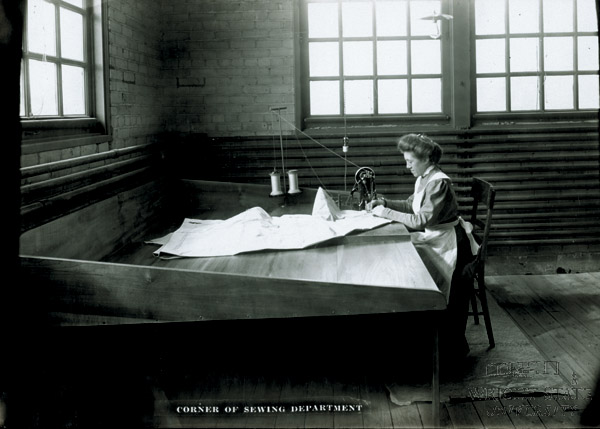

Ida Holdgreve was born on a farm near Delphos in 1881 to Casper and Sophia Holdgreve, the sixth of nine children. Like most girls of that era she learned how to sew at an early age and was quite good at it. About 1908 Ida moved to Dayton and in 1910 replied to an ad in a Dayton newspaper looking for a “plain sewer”. As an accomplished seamstress Ida figured she could handle that job and applied. To her surprise, the newspaper had misspelled “plain” when it should have been spelled “plane”. Ida had applied to be the seamstress at the new Wright Brothers Airplane Factory. The Factory started at the Speedwell Motor Car Company while the new factory was being built. Ida started her “plane” sewing career in a small room there. For the next five years Ida sewed the fabric covering for Wright Brothers planes. She recalled that she sewed “cloths for the wings, stabilizers, rudders, fins and I don’t know what all.” She learned the craft from Duval La Chapelle, Wilbur’s mechanic in France. He taught her how to cut and sew the fabric so it would stretch tight over the frame and not rip. Her work in the new aerospace industry earned her $8-10 per week.

Wilbur Wright died in 1912 of typhoid fever and with the loss of his brother and health problems, Orville’s interest in the company lagged. In 1915 the Wright Brothers Airplane Factory merged with the Glen L. Martin Company and became the Wright-Martin Company. Ida continued at the new company until 1920. During World War I Ida supervised a team of seamstresses at the Dayton-Moraine Airplane Company in nearby Moraine. The factory produced the De Haviland DH-4 plane, the only American built combat plane, and the Dayton-Wright Company was the largest producer of that aircraft. After the war Miss Holdgreve sewed in the drapery department at Rike-Kumler Company in downtown Dayton. Ironically, Rike-Kumler was the same department store where Orville and Wilbur had purchased the muslin fabric for their 1903 Wright Flyer. Ida retired from sewing at age 71 to care for her sister Sophia. Neighbors recall seeing Ida, at age 75, still mowing the lawn with a push mower.

In November 1969, just a few months after the first moon landing, the woman who played a large part in the early airplane industry took her first flight at age 88. Miss Holdgreve traveled to the Montgomery County Airport to take the flight, a gift from the Dayton Chamber of Commerce. She enjoyed the flight but did comment that it was too noisy. Her first flight drew national attention.

On September 28,1977 Ida was in Delphos visiting her niece-in-law Mildred Holdgreve when she unexpectedly became ill and died at the age of 95. She is buried in Calvary Cemetery in Dayton next to her sister Sophia. In the March 2021 issue of Smithsonian Magazine Ida Holdgreve was recognized for her contributions to the early aerospace industry and was pronounced “America’s first female aerospace worker” by aviation historian Timothy R. Gaffney. He commented that “She was Rosie the Riveter before there were airplane rivets.”

Speak Your Mind